Our little England – baa, baa black sheep

Article by Beth Evans Simmons and Dennis Cass

Summary by Cam Stadtmueller

The pastures and open fields of Harborcreek Township had an entirely different look 175 years ago. The most prominent animal of the early 1800s is seldom seen today – sheep, thousands of sheep.

Beth Evans Simmons and Dennis Cass recently collaborated on a new research paper entitled “Our little England – baa, baa black sheep.” In previous newsletter issues our members have read about the Cass Woolen Mill being a prominent business along Six-Mile Creek in an area called “Factory Gulch.”

Several mill owners are explained in detail beginning with Joseph, Sr. and Olive Backus who “had three mills along Six-Mile Creek” in 1810. Lester and Mary Hays owned the “Fulling mill” for seven years before transferring it in 1844 to John Thornton, John Cass, John Rhodes, Thomas Rhodes, and Joshua Jewett. These men enlarged the woolen mill to the three-story structure you see pictured in the full article and the 2000 edition of the Cass Chronicles by Dennis Cass and Perry Smith, a copy of which is in the Society’s Reading Room. By the 1870s John Cass was sole owner of the mill, and following his death, Martha Halderman, daughter of Joseph Backus, purchased the business. Operation ceased “sometime before 1900.”

The Cass Woolen Mill would not have prospered without the abundance of sheep farmers in Harborcreek Township. Records cited by Simmons and Cass reveal that the 1850 Census enumerated 161 farmers owning a total of 5,321 sheep and sending 14,413 pounds of wool to mills. Samuel Stevens had the largest flock with 400 sheep, and Elijach Owen had the smallest with only three. It is fascinating to read the men’s names and flock sizes, and then compare this to the 1880 chart showing the decline of sheep to 1,700 owned by 50 farmers and wool dwindling to 3,500 pounds for processing.

In the late 1800s, less wool was sent to the Cass Mill for processing and profits declined. WHY? Sheep nibble grass to the roots and ample acreage is needed for rotating them among pastures. Harborcreek farmers were putting more acreage into the fruit industry, especially “hardy Concord grapes,” apples, cherries, pears, and peaches. The few farmers who kept smaller flocks marketed their wool to mills in other areas of Pennsylvania or out-of-state. One well-known processor was the Frankenmuth Woolen Mill in Michigan, which has been in continuous operation since 1894.

Memories of Fishing Blue Pike

One of my treasures is my grandfather’s Coleman Lantern. It was manufactured in the early 1940’s and although I have repaired it many times, it still works as well as new. When we launched from the livery, it accompanied us on every trip. Many boats would collect tightly over the school of pike, each with at least one lantern, giving the impression of a small village when seen from shore. The Coleman was placed over the side of the boat on a hanger inserted in an oar lock. Since it shone exceptionally bright, ours had an accessory to shield our eyes. What was sometimes unpleasantly bright for us was an attraction for minnows – emerald shiners. When they appeared from out of nowhere, my grandfather frantically grabbed the bait net and swung it through the school before they could escape. Our supply of bait would be replenished preventing a fate dread by all fishermen – running out of bait!

One of my treasures is my grandfather’s Coleman Lantern. It was manufactured in the early 1940’s and although I have repaired it many times, it still works as well as new. When we launched from the livery, it accompanied us on every trip. Many boats would collect tightly over the school of pike, each with at least one lantern, giving the impression of a small village when seen from shore. The Coleman was placed over the side of the boat on a hanger inserted in an oar lock. Since it shone exceptionally bright, ours had an accessory to shield our eyes. What was sometimes unpleasantly bright for us was an attraction for minnows – emerald shiners. When they appeared from out of nowhere, my grandfather frantically grabbed the bait net and swung it through the school before they could escape. Our supply of bait would be replenished preventing a fate dread by all fishermen – running out of bait! Lake Erie Adventurers

No matter what the season of the year, there is usually someone thinking or dreaming of what is on the opposite shore of Lake Erie. A recent article published in The Harbor View newsletter, which is published quarterly by the Society and distributed to members, highlighted two spectacular lake crossings. Here are a few more for your reading pleasure.

Due North, Harborcreek Historical Society Newsletter, March/April 2007

Because It’s There, Harborcreek Historical Society Newsletter, May/June 2008

The Ice Walkers, Harborcreek Historical Society Newsletter, May/June 2008

The North East News-Journal printed “Rare Lake Erie freeze shines new light on local men’s adventures” on March 28, 2014. Harborcreek resident and high school teacher Marty Dale has first-hand knowledge of the 1978 crossing of frozen Lake Erie by three North East men. Marty and Archie Wright “manned their CB radios for the night, transmitting every hour to the men.” Who were “the men?” They were Chris Sprague, John Hallenburg, Jr. and Bill Power, who successfully hiked across the frozen lake from Long Point to Freeport Beach March 4, 1978. The trek lasted for 18.5 hours.

Fighting for Peanuts: The Gauge Wars

Not a single cannon was fired, nor a life lost in the conflict known as the Gauge War. It was a conflict of commercial advantage which involved the rights of local government and pitted the citizens of Erie County against Buffalo, Cleveland and New York during the era of railroad development and growth in Pennsylvania.

Earliest railroad activity along the Lake Erie shoreline began in the 1840s, with local investors forming the Erie & North East Railroad. Finished in 1852, this 19-mile section of 6 foot gauge track ran from the City of Erie near 14th Street east to the NY/PA border where it connected with the 90-mile 4’8.5” gauge track of the Buffalo & State Line (New York Central). To the west of the E&NE was the Franklin Canal Company Railroad. Owners of the Franklin Canal Company took several liberties with their contract with the state of Pennsylvania and built a 30-mile 4’10” gauge track connecting the E&NE with the Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula Railroad which began at the OH/PA line. Due to the difference in track gauge, passengers and freight traveling along Lake Erie were forced to change cars twice within the county, once at the NY/PA line and once in the City of Erie.

For the City of Erie, this disruption in rail travel was part of a plan. In an effort to spark industrial and economic growth at the point of the harbor, Erie planned to cut off Buffalo which connected to New York City via the Erie Canal, and connect the Erie harbor to the Atlantic seacoast through Philadelphia via the Sudbury & Erie Railroad. Key to the success of this plan was the incompatibility of the E&NE with the Ohio and New York rail systems which necessitated stoppage within the City of Erie.

By April 1853, railroad interests in Ohio and New York realized the value of uninterrupted rail travel along Lake Erie and felt pressure from stakeholders to improve efficiency of operations and dividends. They began to buy up stock in the E&NE with the intent to standardize the track gauge in Erie County and enable continuous travel from Buffalo to Cleveland. Coincidentally, at the same time the PA General Assembly repealed the 1850 Gauge Law which forbade use of the Ohio 4’10” gauge east of Erie. To the satisfaction of the Ohio and New York railroads, standardization of gauge along the lake shore was now possible.

Erie & North East stakeholders underestimated residents’ willingness to wage war against the railroad to protect their commercial interests and the rights of local government. The City of Erie passed an ordinance in July declaring the 4’10” gauge a public nuisance east of State Street, and the railroad’s request to allow gauge change was rejected in November. When the railroad began making necessary changes to the E&NE tracks December 7, 1853, the City of Erie and Harborcreek Township responded immediately. Erie Mayor Alfred King deputized 150 “special police” who quickly set to work removing the rails and bridges. In Harborcreek, the township commissioners used the change to justify destroying the railroad where it interfered with Buffalo Road, the primary public highway through northeast Erie County. In the three places where the rails crossed Buffalo Road and hindered wagon travel, Harborcreek Township commissioners ordered the rails removed and the railbed plowed under. Destruction to the rails in Erie and Harborcreek created a 7-mile break in travel and during the next two months passengers and freight were transferred between Harborcreek and Erie by stages, wagons and sleighs.

To Erie’s opponents, the City’s resistance was an act of foolishness which disrupted travel, commerce and mail. Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune and onetime Erie resident, called for a boycott of all Erie hospitalities by travelers who were forced to cross the 7-mile “isthmus of Erie.” He and others argued that the city’s sole ambition was to protect its trade of peanuts, popcorn, candies and pies which were sold to travelers. (For this reason, the Gauge War was also referred to as the Peanut War.) Luckily for Erie, President Franklin Pierce resisted pressure from the New York and Ohio railroad interests to suppress Erie’s resistance with federal troops.

December 17th the E&NE procured an injunction from the federal district court in Pittsburgh, but the threat of imprisonment did not deter those committed to nuisance abatement and repeat removal of tracks and bridges continued with the support of local government as well as PA Governor William Bigler. In his annual message to the assembly in 1854, Governor Bigler explained,

It so happens that PA holds the key to this important link of connexion between the East and West, and I most unhesitatingly say, that where no principle of amity or commerce is to be violated, it is the right and the duty of the State to turn her natural advantages to the promotion of the views and welfare of her own people. (Pennsylvania Archives, Fourth Series, Papers of the Governors, Volume VII, 1845-1858, pg. 651.)

A confrontation between Harborcreek residents and railroad officials and laborers on December 27th stands out among the rest. While Harborcreek Township officials supervised the destruction of the E&NE tracks for the fifth time in three weeks, a train full of railroad officials, tracklayers and laborers arrived from Buffalo. During the confrontation that followed, Harborcreek farmer William Davison was felled with a pick, George Nelson received a gunshot wound to his head when one of the men from New York drew his pistol, and, if it weren’t for the misfiring of the pistol, William Cooper may have been the first casualty of the “war.” In retaliation, Harborcreek men stormed the train, and the Buffalo men fled the impending riot on the train with which they arrived.

A confrontation between Harborcreek residents and railroad officials and laborers on December 27th stands out among the rest. While Harborcreek Township officials supervised the destruction of the E&NE tracks for the fifth time in three weeks, a train full of railroad officials, tracklayers and laborers arrived from Buffalo. During the confrontation that followed, Harborcreek farmer William Davison was felled with a pick, George Nelson received a gunshot wound to his head when one of the men from New York drew his pistol, and, if it weren’t for the misfiring of the pistol, William Cooper may have been the first casualty of the “war.” In retaliation, Harborcreek men stormed the train, and the Buffalo men fled the impending riot on the train with which they arrived.

After January 1854, a series of court decisions and legislative acts tipped the balance of power in the railroads’ favor, and by late 1856 a track of continuous gauge connected Cleveland to Buffalo; the passage of trains through the “isthmus of Erie” was uninterrupted.

The change in gauge did not stunt growth of the City of Erie as residents had feared; during the late 19th and 20th centuries, Erie became a commercial and industrial center on the Great Lakes, even though it would never reach the size of Buffalo or Cleveland. The Gauge War remained a topic of serious debate for many years after, and today is an oft-cited example of confrontation between the railroads and the local communities that they served.

Featured artwork by local artist Bryan Toy.

Harborcreek Race Tracks

One of our newsletter articles on the Thunder Bowl Track at Iroquois and Nagle contained information provided by former driver Dave Turner (Car 222). Included in his response was a brief report on the Highmeyer Road Track. In winter, after leaves and vegetation have disappeared, remnants of the track can be spotted on the west side of the road, slightly north of Dutton Road, which is where the Zack Family lived. Mr. Dick Zacks, a race enthusiast, built and operated that short-lived track. Memorable to Dave were its long straight-aways and that “it was a really nice track”.

Shorty the flagman was another prominent figure and important person who came to mind at the mention of this track. Although his real name escapes Dave, he recalls that he had been the flagman at Sportsman Field, which was a NASCAR track, featuring some excellent drivers and required a first-class flagman. Apparently, he also impressed Dick Zacks, who recruited him.

Finally, Dave remembers an occasional drop-in from around the corner – Mrs. Zacks in her J2Allard Roadster!

For you former racing fans and history buffs, the names taken from a 1950’s era list might be of interest. They are local but do not pertain specifically to Harborcreek alone.

| Joe Sharkey, Big 5 – ’34 Ford

Eddie Boga, 8 Ball – ’35 Ford Bob Boga, 22 – ’47 Ford Dick Bonnell, 52 – ’46 Merc Paul Deison, 9 – ’47 Merc Jack Foster, Sweet 16 – ’39 Chev Jack Davidson, OU-1 – ’47 Merc H. Eisman, 14 – ’39 Ford George Radford, 15 – ’38 LaSalle Dick Linder, V-2 – ’40 Ford Dick Perry, 1 – ’39 Ford Tiny Stoltz, F-86 – ’46 Ford Bob Lyle, 9 Ball – ’38 Buick Dick Abbott, 38 – ’41 Ford Bob Tobin, 21 – ’46 Ford Tom Dill, 51 – ’47 Merc Red Blitz, 6 – ’38 Ford Bill Hansen, Lazy 8 – ’50 Olds Carl Watkins, 53 – ’46 Ford Chuck Landers, Big 7 – ’34 Ford Fred Peters, 11 – ’38 Buick Bob Snyder, 1/4 – ’39 Ford H. Aillyes, 4-11 – ’46 Ford

|

Barney Fier, Double O – ’47 Ford

Bob Gauthier, 13 – ’40 Ford Tony Reitz, 49 – ’46 Chev Carl Ahlbrandt, 4363 – ’47 Merc Clyde Porter, PA-5 – ’40 Ford John Adler, 46 – ’39 Ford Jim Houser, Big 8 – Ford Ted Nouser, Crown 7 – Ford Bill Toomey, 666 – ’37 Pont Bill Riggs, 15 – ’35 Ford Cliff Root, 71 – ’40 Ford Buzz Anderson, 735 – ’47 Merc Ralph Klett, 141 – ’39 Ford Dick Haig, 96 – ’39 Ford Frank Hlifka, 25 – ’46 Ford Roger Blount, 999 – ’40 Merc Bob Allen, K-9 – ’47 Merc Art Tubbs, 60 – ’36 Ford Mike Komisarski, 7 – ’50 Olds Dave Turner, 222 – ’40 Ford Norm Haibach, Dbl 2’s – ’41 Ford Gary Dolph, 408 – ’46 Ford

|

Folly or Just Victorian Pleasures

By W. Richard Cowell, Esq.

Located in Harborcreek Township overlooking the banks of Lake Erie stands a small turret, the stone walls of which reach not much more than eleven feet high and are capped by a wooden conical roof. It has an arched doorway facing the lake, a circular window opening approximately halfway up, which would catch the morning sun, and an arched window opening, which would catch the afternoon sun. There are no signs that any of these openings ever had windows or doors attached but, rather, are bare openings in the walls. The interior is about eight feet in diameter with stone-mortared walls about twenty inches thick. It has essentially stood undisturbed for the past 100 or more years. Its purpose is not obvious, and most viewers will guess that it had some adventurous or playful use in its design.

Located in Harborcreek Township overlooking the banks of Lake Erie stands a small turret, the stone walls of which reach not much more than eleven feet high and are capped by a wooden conical roof. It has an arched doorway facing the lake, a circular window opening approximately halfway up, which would catch the morning sun, and an arched window opening, which would catch the afternoon sun. There are no signs that any of these openings ever had windows or doors attached but, rather, are bare openings in the walls. The interior is about eight feet in diameter with stone-mortared walls about twenty inches thick. It has essentially stood undisturbed for the past 100 or more years. Its purpose is not obvious, and most viewers will guess that it had some adventurous or playful use in its design.

The most common thoughts are that it was to watch or signal ships upon the lake, or it was built as a play spot for children, but no one is ever quite satisfied with their guesses. To find the answer, it helps to look to the people who would have owned and used the property shortly before and after 1900.

The Galbraith family, William A. and Fanny, owned several properties in Erie County, including their primary home, the site of what is now the Woman’s Club of Erie on the southeast corner of West Sixth Street and Myrtle Street. As early as 1852, William A. Galbraith had part ownership in portions of Irvine’s Reserve, in Harborcreek Township, consolidating his interests by about the mid-1880s. The Galbraiths created a “cottage” or summer residence along the banks of Lake Erie near Six-Mile Creek, which included the parcel upon which is now found the stone tower. Fanny Galbraith survived her husband, William, and upon her death, passed title to the properties unto her sons, John W. and Davenport Galbraith. The sons separated their titles, with Davenport and his wife, Winifred, taking the West Sixth Street and Harborcreek properties.

Winifred D. Galbraith was an avid reader and a talented amateur artist. She had the stone tower built as a suitable place for her to sketch and paint, as well as read, giving her shelter from the sun or rain when the occasion required while giving her access to the land and seascape. It was not unlike the Victorians to go to such extravagant measures to provide for those small pleasures.

The stone tower still stands, children playing and occasional picnickers about. There is probably no one alive who can remember it having last been used as an artist’s shelter or some good-weather reading spot, but that was its original purpose.

However, “Folly,” or not, it’s still not a bad idea!

All information for “Tales & Treasures” comes from source material found in the archives of the Harborcreek Historical Society. Such material may be based on facts, family legends or popular history. Anyone having substantiated conflicting data please contact the Society.

Circus Impacts Harborcreek Township

By Harold L. Kirk

Back in the early 1900’s when young people “ran away to join the circus” what did they do during the off-season? For a true runaway, it was like they say, “you can’t go home again.” Many circus performers and workers tended to spend the off-season near where the circus was wintering over so that they could work at the quarters, full or even part time, helping to care for the animals or maintaining the equipment and barns. For the Cole Brothers employers this meant living in Harborcreek from November through to April each season. Some even took jobs with local businesses or on farms nearby and, in addition, local people were hired to help at the quarters thus greatly affecting the economy of the area. Following are some examples taken from the Erie Newspapers of the time that illustrates the impact of the circus on our small village:

The winter quarters of the Cole Brothers shows, at Harborcreek, near this city, from the blacksmith shop to the harness room and wagon shop to the wardrobe department, is one of the busiest spots in the vicinity. It is hard for the layman to conceive what the wardrobe department accomplishes during the winter months, for he does not know that this show has a complete new wardrobe every season. Miss Ada Forbes, wardrobe mistress, and her 12 assistants are busy as the traditional bees. Imagine a dressmaker measuring elephants, camels, horses, ponies and even monkeys for clothing as well as making costumes for the lady and gentleman performers. There are over 2000 pieces in the wardrobe.

***

Miss Chambers, teacher of the primary rooms treated her pupils to a visit to Cole Brothers Ring barn Thursday afternoon. The utmost order was preserved and the little ones voted the afternoon well spent.

***

Cole Bros. show leaves Harborcreek on April 20. Our little town is quite a busy place at present. Scores of beautiful horses consisting of eight and ten horse teams are being exercised, also the chariot horses.

Special worship services were frequently held at the First Presbyterian Church for the circus personnel and Harborcreek lawyer R.J. Firman often represented the interests of the Cole Bros. employees. Nancy Brown says that her Mother (local teacher, Lillian Davison) was named after Cole Bros. circus equestrienne “Lill.”

With all the animals in the menagerie (some very large) we know there was an environmental impact on the community but as you can see there were also economic and social aspects to having the circus winter over in our area.

All information for “Tales & Treasures” comes from source material found in the archives of the Harborcreek Historical Society. Such material may be based on facts, family legends or popular history. Anyone having substantiated conflicting data please contact the Society.

Anatomy of a Mill

By Harold L. Kirk

Nowadays when people think of an old time mill, they picture in their mind a water wheel and a small, quaint, wood or log building nestled beside a picturesque stream. Such mills of course did exist. They were called custom mills and for the most part served one family or a group of farmers in a small area. The miller usually took a percentage of the grain for providing his services.

When we see pictures however, like the one shown here of Harborcreek’s Empire Mills on Four Mile Creek or Neeley’s Mill on Twelve Mile Creek, we wonder why they were so large and contained three or four floors when the custom mills were only one or two small rooms. These large mills were called merchant mills. They ground grain and produced flour for profit and export.

The milling process required to produce commercial grade flour is a lengthy one. The grain travels up and down from floor to floor and back and forth its length as many as seven times. Starting at the bottom of the mill the grain is picked up by a series of buckets attached to a conveyor belt and taken to the top floor and put into bins to wait its turn to be processed. When the bin is opened, gravity allows the grain to flow down to the main floor to be ground by millstones or by rollers as was the case in the Empire Mill. Three or four trips up to the second or third floor and back down were required as sifting and cleaning of the ground grain was needed following each rolling or grinding operation. To transverse the length of the building wooden conveyors or augers were used to move the ground grain to various sifters, separators, scalpers and graders where dirt, stones and bran are removed and various grades of meal and flour are collected. The last trip down to the main floor is then made where the final product is packaged for shipment or for sale at the mill store. The Empire Mill had a capacity of seventy-five barrels a day and was one of Harborcreek’s most profitable industries.

On August 3, 1883, about daybreak, fire was observed issuing from the windows of Cooper’s large flouring-mill on Four Mile Creek. Accelerated by explosions of fine flour dust, the fire had made such headway that it was impossible to save the building even though willing bystanders formed a bucket brigade.

The loss was estimated to be $30,000, upon which only $11,000 was covered by insurance. A few days earlier Mr. Cooper spoke of increasing the insurance, but his son advised him to wait. I guess his son never heard the expression, “Father knows best.”

All information for “Tales & Treasures” comes from source material found in the archives of the Harborcreek Historical Society. Such material may be based on facts, family legends or popular history. Anyone having substantiated conflicting data please contact the Society.

The Harborcreek Future Farmers of America, 1955-1958: A Brief Overview of Its Operational Structure

By Fred Harris

I was accepted into the Harborcreek Chapter of the Future Farmers of America (F. F. A.) in the fall of 1955, and so began an experience that would provide me with a base that I would find myself drawing on throughout out a life time.

Vocational Agriculture at Harborcreek High at that time was taught by William Ellwood. Time would show us that he was a fair and knowledgeable man and teacher. He well understood young boys, and was more than willing to tolerate their shenanigans; as long as they did not get out of hand. He had respect for all of “his” boys. They, in turn, respected and trusted him.

A Vo. Ag. student was required to carry at least one agricultural orientated project, then each succeeding year the student was required to add at least one additional project, so that in the fourth year one would have at least four active projects.

A typical class ran two periods – one usually of classroom theory, and one of farm shop or field trips. While most students had to move from class to class within the confines of the school building each day, we got to walk outside to get to our class ( which was held in the annex); and then once there, who knew where we’d end up.

There were three degrees of chapter membership in the Harborcreek Chapter of the Future Farmers; Green Hand, Chapter Farmer, and State farmer. The fall of “55” saw myself as well as 11 other classmates initiated into Green Hand. After the last of the “tests” were passed, we were awarded our bronze Green Hand pin at a solemn ceremony, which in part consisted of sitting on a block of ice and reciting the FFA Creed. A Creed that I, after 55 years, can still remember. I often wonder why.

With the approval of a chosen project, we were given a project record book. In this book we kept all records of our project work, such as hours worked on the project, amount of money expended, types of machinery required and cost involved, as well as comments and observations and any profits/ losses made. Our grades were based in great part on these records and success of goals set.

Vocational Agriculture class ran all year around, like a farm would, unlike “normal” school class’s that began in September and ended in May. Mr. Ellwood would make unannounced visits to class members to observe our project (s) and answer any questions we may have. He would check our Project Books and make recommendations as to how we might improve our operations. These visits could occur at any time, but usually happened during summer vacation.

Vocational Agriculture class ran all year around, like a farm would, unlike “normal” school class’s that began in September and ended in May. Mr. Ellwood would make unannounced visits to class members to observe our project (s) and answer any questions we may have. He would check our Project Books and make recommendations as to how we might improve our operations. These visits could occur at any time, but usually happened during summer vacation.

Throughout some 40 years of my working career as a hospital planner, I often drew from the teachings of my years in F.F.A.. What, you may ask, did the teaching of farming have to do with helping one in such a profession, or any profession, so removed from the land? The teachings of F.F.A. taught, (and still does) among many other things, (1) work ethics, (2) cooperation with others, (3) hope of progress through ones labor, (4) leadership, (5) respect (for oneself & others), (6)responsibility ( to oneself, family & community) (7) organization, (8) dreams & development of those dreams. Ah…those were the days.

Where Men and Boys Became Soldiers: The History of Camp Reed

By Eric Marshall

By the time Abraham Lincoln took the oath of office as President of the United States on Monday, March 4, 1861, the national upheaval of secession was a grim reality. Jefferson Davis had been inaugurated as the President of the Confederacy two weeks earlier and nerves were raw. Despite the fact that, in his address, Lincoln called for calm and ”the better angels of our nature,” the following month Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor was forced to surrender following bombardment by Confederate forces and the country was at war.

In Erie the news of war was greeted with great patriotic fervor. Local government bodies responded with resolutions in support of the Union. Letters and editorials appeared in the newspapers urging citizens to fly their flags. When the word was received that troops were needed, one local citizen, John W. McLane, on April 21, issued a call for volunteers for immediate service in the National Army and within four days twelve hundred men, from Erie, Crawford and Warren counties had assembled at the City of Erie.

The grounds selected for the local encampment were east of the city on the north side of Buffalo Road and were the original Erie County Fair Grounds. They were purchased by the Fair Association in 1860 and fairs were held there in 1860 and 1861. Today this would be the land that is on the northwest corner of Buffalo Road and Franklin Ave. immediately across from the Jack Frost Donut Shop on Buffalo Road. The land ran from Buffalo Road to the railroad tracks and was known as “Camp Wayne” after General Anthony Wayne who died in Erie in 1796. There were some display buildings on the fair grounds that were loosely constructed. They faced the north and east and were used by the soldiers as temporary shelter.

McLane was no stranger to military affairs. In 1859 he had organized a local group known as the “Wayne Guard,” a volunteer company whose duties were mostly ceremonial. This company became the nucleus of the new regiment which was known as the “Erie Regiment.” The men had no uniforms and so the ladies of the city organized and quickly raised funds and made the men uniforms which consisted of a jacket and pants of blue and a shirt of yellow flannel. Quite an accomplishment which took just under a week!

On April 27 McLane was elected the Colonel of the regiment, Matthias Schlaudecker was elected Major and Strong Vincent, a private in the Wayne Guards, was appointed Adjutant. The next day the regiment headed by rail to Pittsburgh having been organized in just one week.

The “Erie Regiment” never saw any action on the battlefield. They were disbanded following a three month encampment in Pittsburgh and the expiration of their term of service. They returned to Erie via railroad and were greeted with a picnic provided by local citizens.

The “Erie Regiment” had scarcely been disbanded when the news of the disaster at Bull Run on July 21 aroused the nation to a new sense of danger. Several days later Simon Cameron, Secretary of War, issued a call for regiments to be formed for three year’s service. Colonel McLane volunteered to raise a regiment in Erie and in less than five weeks nearly a thousand men had responded, embracing nearly three hundred from the old “Erie Regiment.” They rendezvoused at “Camp Wayne,” now renamed “Camp McLane,” where they set up camp life. The fair buildings were converted into bunk houses and a drill field constructed where at the head stood a large flag pole. Again, elections were held and McLane was elected Colonel and Strong Vincent, Lt. Colonel.

The new regiment attracted men from not only Erie, Crawford and Warren Counties but Venango and Mercer Counties as well. On September 8th, the regiment was mustered into service for the United States and the name was changed from the “Erie Regiment” to the 83rd Pennsylvania Volunteers. This regiment would go on to fight in a whole list of battles including Antietam, Gettysburg, the Wilderness Campaign, Spottsylvania, the Siege of Petersburg and was present for the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House. The 83rd was disbanded at Harrisburg on July 4, 1865 having suffered total losses of 435 officers and men.

On August 30, 1861, Matthias Schlaudecker, who had been a Major in the “Wayne Guards” and also a Major General of Militia in Pennsylvania, wired Governor Andrew Curtin for authority to recruit a new regiment from northwestern Pennsylvania. Upon receiving approval, Schlaudecker set out raising a second regiment from the Erie area. Schlaudecker sought support of Thomas M. Walker, a civil engineer from Erie and George A. Cobham, Jr. of Warren in raising the new regiment. He also renamed “Camp McLane” after a prominent Erie citizen, General Charles M. Reed, who at the time of his death in 1871, left an estate of nearly fifteen million dollars. The mansion that C. M. Reed built is located on the northwest corner of Perry Square and is known today as “The Erie Club.”

Schlaudecker realized that morale among his men would greatly improve if they had proper food and housing. The old fair buildings were upgraded and great stoves were requisitioned to keep them warm. Headquarters were established in newer buildings near by Camp Reed. Schlaudecker, himself born in Bavaria, filled the regiment with a cross section of men with many men of German and Irish lineage found in its ranks but the bulk were native born. Schlaudecker ran the camp under military law and obtained new percussion cap weapons for the guards. A hard taskmaster, every minute of every day was filled with prescribed duties. Food was a ration of hard bread, beef or pork, beans, coffee and sugar. Those who were closer to home enjoyed food and clothing deliveries from family members. Those from outlying areas were not so lucky.

A typical day at Camp Reed under Schlaudecker’s command would start with falling into ranks at six-thirty for muster and inspection. Breakfast was at eight and sick call at nine. The regiment was divided into companies of one hundred men each and they would compete for awards in drilling. Drill would last until lunch and then continue until dress parade where the regimental band would be stationed behind Schlaudecker and would play while he would review the troops. A school for officers was established and it met daily. The result of this discipline was a splendid “esprit de corps.” During the evening

hours the officers would meet and would frequently draw up “Resolutions” concerning the war effort which would appear in the local papers.

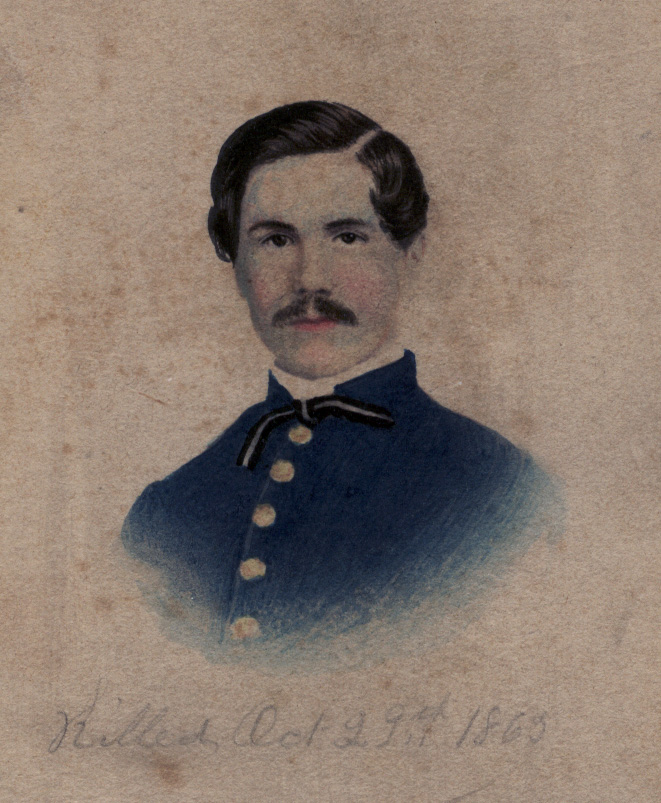

Marvin D. Pettit, 1st Lieutenant, 111th P.V.I. Killed in action October 29, 1863.

On January 24, 1862 the regiment was filled and elections were held with Schlaudecker being elected Colonel, George A. Cobham, Jr., Lt. Colonel and Thomas M. Walker, Major. On February 24 marching orders were received and the regiment was to move to Baltimore via Cleveland, Pittsburgh and Harrisburg on the railroad. On February 27 they received their rifles and the regiment then marched across the capital grounds to receive their colors from Governor Curtin. The regiment was commissioned as the 111th Pennsylvania Volunteers and fought at Antietam, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg as part of the Army of the Potomac and then, as part of the Army of the Cumberland, at Wauhatchie, Lookout Mountain, Peach Tree Creek, Atlanta, Savannah, Raleigh and the surrender of Johnson’s Army. They also participated in the “Grand Review” in Washington, D. C. on May 24, 1865. The Regiment was mustered out of service on July 19, 1865. Their total losses were 304 officers and men.

One true moment of glory for the 111th occurred when they were ordered to “press” into the City of Atlanta to determine the strength of Confederate forces. Finding little opposition,

the column reached City Hall where it formed a line of battle, unfurled its battle-stained flags and received the surrender of the city. Lt. Colonel Walker, then Commanding Officer of the 111th, took the city in the name of General Sherman who telegraphed President Lincoln that “Atlanta is ours, and fairly won!” The whole north burst into enthusiasm over the great victory. The population of northwestern Pennsylvania was exceptionally proud of the accomplishments of its regiment.

Camp Reed remained vacant until the last and final regiment for the war effort was raised,

commencing in the fall of 1862. This regiment, consisting of seven companies from Erie County, also had one company each from Crawford, Warren and Mercer Counties. They rendezvoused at Camp Reed in the late summer of 1862. Hiram L. Brown of Erie was elected Colonel. David B. McCreary, also of Erie, was elected Lt. Colonel and John W. V. Patton of Crawford County was elected Major; Colonel Brown had served in the “Wayne Guards” prior to the war and also as a Captain in the three months’ Erie Regiment and as a Captain in the 83rd where he had received a severe wound at the Battle of Gaines Mill. Lt. Colonel McCreary had also served in the “Wayne Guards” and had been a lieutenant in the Erie Regiment.

At the time of the organization of the regiment there was an urgent and immediate need of troops in the Army of the Potomac. The regiment departed Erie on September 11, 1862 for Harrisburg and then Chambersburg having received almost no drill instruction by Colonel Brown who was still suffering from his wound. The Army of Northern Virginia was crossing into Maryland in preparation for a battle that would be fought along Antietam Creek. The regiment, now commissioned as the 145th Pennsylvania Volunteers, without arms and scarcely any knowledge of military duty, were sent to the front. Here they were issued antiquated muskets but no training in how to use them.

The morning of September 17 found the regiment at the far right of the Union line at the Battle of Antietam facing a force commanded by General Thomas (Stonewall) Jackson. The fighting was intense but the 145th held its ground and the regiment awoke the next morning to find that the enemy had retired from the fight.

The 145th saw action as part of the Army of the Potomac at Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, the Wilderness Campaign, Cold Harbor and the Siege of Petersburg, and was present for the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House. The 145th also participated in the “Grand Review” in Washington on May 23, 1865. The regiment was mustered out of service on May 31, 1865. Their total losses were 422 officers and men.

Following the war Camp Reed fell into disrepair. The buildings were eventually torn down and the land sold to Mr. H. C. Shannon who held it until his death. By 1896 the land was part of his estate. To this day, no marker is in place to commemorate this historic plot where so many military careers commenced, where many soldiers wished their loved ones well and then never returned to see them again, and where the “art of war” was taught in Erie County.